The necessity of lament and doubt

Soong Chan Rah's Prophetic Lament and Anna Gazmarian's Devout

Lament is having a heyday in some evangelical and post-evangelical subcultures, and for good reason. It’s a corrective to the triumphalism of American Christianity as well as a necessary response to the pain and evil of both current day and historical events.

Those who are suffering have always known the power of lament, though.

I can’t claim that I’ve ever truly suffered, given that my life has always been comfortable. Yet minimizing my own struggles because I don’t want to appear callous to the world’s tragedies is not an honest accounting, either. Emotional pain and mental anguish and physical exhaustion and spiritual desolation are real, and we would feel less alone if we talked about these things more.

Freshman year of college—honestly, most of college—was one such time for me. In my last post, I wrote about taking a course called The English Bible during my freshman fall, and how it almost broke my faith, though over the course of years, the disillusionment it granted me became a path to a more authentic belief.

But one thing it did give me in the moment was the New Revised Standard Version of Lamentations Chapter 3. I had never read the NRSV edition of the Bible before, and in my evangelical upbringing, I’d only heard verses 22-23 taken out of context as a praise of God’s goodness: “Because of the Lord’s great love we are not consumed, for his compassions never fail. They are new every morning, great is your faithfulness” (Lamentations 3:22-23 NIV).

But read in context, they were so much more powerful.

Consider the verses leading up to them, in particular:

“He has filled me with bitterness, he has sated me with wormwood. He has made my teeth grind on gravel, and made me cower in ashes; my soul is bereft of peace; I have forgotten what happiness is; so I say, ‘Gone is my glory, and all that I had hoped for from the Lord.’ The thought of my affliction and my homelessness is wormwood and gall! My soul continually thinks of it and is bowed down within me.” -Lamentations 3:15-20 NRSV

That passage gave words to the turmoil of my soul in those days: bereft, yes, and bowed down. Throw in some wormwood and gall for good measure. I don’t know if I had ever encountered such honesty in Scripture—not that other parts weren’t true, but the writer of Lamentations offered up a kind of vulnerability I had never seen before.

For a long while, this was one of the only passages of the Bible that I could stomach reading. And I could stomach reading—indeed, I could find hope in—the verses immediately following that passage only because I trusted the devastated soul who wrote verses 15-20.

Verses 21 reminds me of the modulation from minor key to major key, setting up verses 22-23:

“But this I call to mind, and therefore I have hope: The steadfast love of the Lord never ceases, his mercies never come to an end; they are new every morning; great is your faithfulness.” -Lamentations 3:21-23 NRSV

That entire chapter of Lamentations remains one of my favorite passages of Scripture. I return to it, over and over, in times of sadness or unbelief or hopelessness.

Thus, it was with great anticipation that I finally read Soong-Chan Rah’s Prophetic Lament: A Call for Justice in Troubled Times, a meditation on Lamentations, earlier this year. First published in 2015, this is yet another book that illustrates how Rah has often been ahead of his times.

He writes that the American church has lost touch with the Scriptural imperative to lament. Instead, we focus solely on celebration and praise, leading to an unbalanced and dishonest spirituality.

Our disconnection from lament is a disconnection from history, as well as a discomfort with unpleasant emotions, be they shame, guilt, or sadness. We deny that others have suffered, particularly the Indigenous peoples from whom our nation’s lands were stolen and the Black people upon whose unpaid labor our nation’s wealth was amassed.

We don’t lament over our country’s sinful foundations and the American church’s complicity because we don’t want to admit that we’ve been beneficiaries (those of us who aren’t Indigenous or Black, that is). We like to think that we are self-made people, historically untethered, starting from the ground up. Self-examination is not our nation’s favorite pasttime.

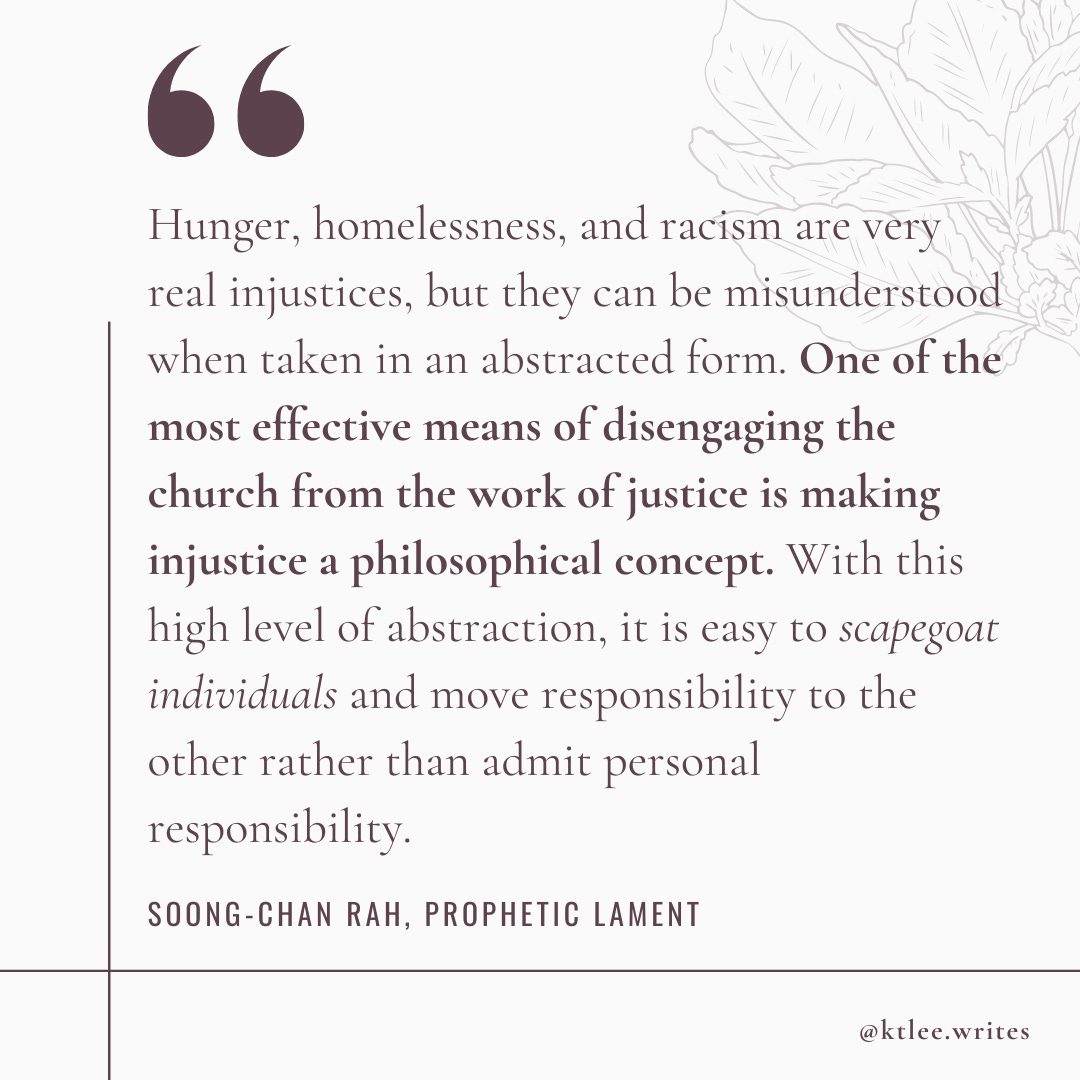

Yet Rah forces us to look critically at the ills of our nation and at our own role in them:

We are content to stay on the plane of abstraction because it does not implicate our own selves. Rah writes,

“We write checks to end human trafficking but lack concern for how our demand for cheap, disposable clothing generates a larger system of exploitation. We forget that hunger in Africa has any connection to the history of Western coloniailism from which we in the West have significantly benefitted. We are oblivious to the need for corporate responsibility to address colonial abuses in previous centuries. ...We abstract injustice, allowing ourselves to believe we no longer have a direct hand in it.”

Throughout the book, he reminds us that there is a better way, as modeled by the writer of Lamentations, to remember our sullied history, confess our complicity, lament and grieve over the pain that has been caused, and make reparations. If we allowed more voices to shape the discourse in the American church about race and history, the church wouldn’t be stuck in such a willfully ignorant place.

Mirroring exactly what Rah argues in the book, growing up, I had only been taught the glory of Lamentations 3:22-23, without the teeth-gnashing and torment of the first part of the chapter.

We want the joy without the suffering, the celebration without the grind. We want to skip ahead to the good parts.

But separated from the human anguish of verses 1-21, verses 22-23 can read like a platitude. They’re a Hallmark greeting card, divested of their moral courage.

Lamentations doesn’t try to silence the suffering. It gives space for grievance and rage and bitterness. If the author of Lamentations eventually arrives at faith, it’s a hard-won faith, a faith that has traveled to the abyss and back.

—

Recently, I read Anna Gazmarian’s book, Devout: A Memoir of Doubt, in which she mentions Rah’s Prophetic Lament in passing. Her memoir feels fitting to review alongside Rah’s book, because it also contends with the church’s failure to deal well with suffering—in Gazmarian’s case, with doubt and mental illness.

While I enjoyed her capable storytelling and appreciated her shining a light on mental illness (and related strongly with how allergic she became to certain Christian ways of speaking), I wanted more substance, especially about why she didn’t entirely turn away from faith. I wish she had looked to Christians of color more for spiritual nourishment, but I understand that may not be part of her story, as important as it is to mine—it just seems like a missed opportunity to highlight how there have always been saints who resist being co-opted by the halls of power. Then again, this is not a very political analysis of power in the church; it’s truly just Gazmarian telling her moving story. I appreciate that she normalizes doubt and mental health struggles, and her openness about her treatment journey for bipolar disorder is refreshing (especially for a book about faith).

This would be an excellent introduction for someone who is starting to question evangelicalism and could use a friendly, relatable voice to journey with. After you read Devout, I’d recommend all of Rachel Held Evans’ books, Soong-Chan Rah’s The Next Evangelicalism, and—oh wait, I already put together a whole post of these recs.

Which authors have been helpful for you in your doubt / lament / faith journey?

Thanks for this. I definitely agree it's important that Lamentations 3:22-23 is not where the book starts. I'm curious what you think about the fact that it's also not where the book _ends_. If I remember from my previous read-through, Lamentations 4 and 5 seem to be in a bleak mindset not that different from 1 and 2. How do you account for the turn _toward_ hope in chapter 3, and then seemingly back _away_ from hope?