Recalling my freshman year of college fills me with a sort of pity for the naive, idealistic, bright-eyed girl from Iowa who believed that goodness and integrity were values that reigned supreme. How excruciatingly slowly Harvard will disabuse you of this notion, I want to tell her.

But disillusionment, which for many years felt like A Very Bad Thing, now feels like a necessary part of my journey: a triple disillusionment regarding the way the world works, the faith of my youth, and the Asian American Dream, a shattering of the false in order to clear soil for planting new seeds.

One accelerant towards that disillusionment was a class I took my freshman fall. When I found out I could fulfill a core English requirement by taking The English Bible, I immediately signed up. Read my Bible like a good Christian while getting course credit? Win-win!

Projecting over the heads of hundreds of students, Professor Robert Kiely’s sonorous voice filled the lecture hall with expositions of Genesis, Ruth, and the Gospels. I was captivated by his storytelling and exegesis; he read and interacted with Scripture from an entirely different posture than the pastors and Bible study leaders of my childhood. Professor Kiely held Scripture in high regard; even, perhaps, considered it the Word of God, but he did not teach it as literally true.

He resembled no Christian I had met before, as he didn’t view Scripture as infallible, but he had a reverence for the Bible that I couldn’t place. He taught us about the various potential human writers of Scripture and the similarities of the Hebrew Bible to other ancient texts. I couldn’t figure him out. (I later found out that he’s a Benedictine oblate, which goes to show how narrowly my evangelical-informed mind viewed the Christian world).

Yet given how calcified my conceptions were at the time of truth vs. heresy, Biblically-sound vs. unorthodox, and right vs. wrong, Professor Kiely’s persuasive reading of Jonah as fable and Job as parable shook the pillars of my faith: What if the Bible wasn’t literally true? Given Protestants’ disproportionate emphasis on the Bible as a (if not the) primary way God is revealed to us, this sent me spiraling. What could I even trust any more?

My relationship with the Bible changed after that course. The problem was that despite my doubts about its reliability, I didn’t want to discard it entirely. There were passages that continued to astound me with their wisdom, beauty, and grace. And Scripture contains the story of Jesus, who remained a life-altering presence. I just couldn’t get behind the inductive Bible study that was popular in evangelical spaces at the time (and today), where we’d use different color pens to highlight key words and patterns and attempt to draw meaning from the fact that the word “drink” is mentioned four times here and “sheep” is mentioned four times there. I went through the motions regardless because I wasn’t taught any other model of interacting with Scripture.

Over the years, there have been some limited ways that I’ve found that help me read the Bible in a life-giving way, but it’s still been difficult to contend with passages in Scripture that seem to excuse genocide or violence or patriarchy.

Enter Marilynne Robinson’s recent book, Reading Genesis. Robinson, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of the novel Gilead, has long been one of my all-time favorite writers. From the beginning of Reading Genesis, she names theodicy as the primary problem that readers of Scripture must wrestle with. Drawing parallels and contrasts between Scripture and two Babylonian texts that are often compared to Genesis, the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Enuma Elish, Robinson shows that it is actually revolutionary for the Bible to describe a God who is good and who cares for humans.

Evil and pain are prevalent both in today’s world and in the world of Genesis, but what separates the Hebrew Bible from other ancient texts is the promulgation of a singular, loving, Creator. Yet how does the Bible reconcile an omnipotent and benevolent God with the persistence of evil? Whereas the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Enuma Elish never claim goodness for their gods, Scripture insists on it.

Robinson doesn’t seem interested in proofs. She invites the reader into her interpretation of Scripture, but is comfortable admitting where mystery lingers. Her answer to the question of theodicy, then, is that we humans do not have the ability to see God’s intentions. What appears to be tragic and awful now may work out for good—but perhaps not on a human timescale.

Robinson’s perspective reminds me of the Chinese parable, 塞翁失馬, first recorded in the Huainanzi in the 2nd century BCE, about a farmer who loses his horse. You may have heard of it: A farmer’s horse runs away, and his neighbors pity him, saying, What bad luck! But the farmer’s father says, Who knows if that won’t bring you good luck? And in a series of events, the farmer’s fortune flip-flops, such that what initially appears to be a devastating event turns out to be life-saving.

The Daoist 無爲 (wu wei, or non-action) posture exemplifies acceptance and serenity in the face of inconstant circumstances. In Robinson’s take, our equanimity comes not merely from knowing that the capricious winds of fortune may reverse day to day, week to week, or year to year, but in trusting that God has both benevolent intentions towards humankind and that God has the power to carry out those intentions, as invisible as God’s hands may be to our eyes.

We don’t always see this play out even within the stories of the Bible. Neither the shocking evil nor the hapless blunders that are made in many of the narratives in Genesis are not a reflection of God, but of humanity—a result of God’s hands-off approach.

Thus, those thorny passage of Scripture are not prescriptive, but rather they are an accounting of the events of the time and the imperfect people involved. For example, Robinson explains Lot’s behavior—offering his young daughters to an angry mob hungry for sex in lieu of letting the mob hurt Lot’s guests—as “a failure to know what righteousness would be in this situation.” This line is so powerful because it is relatable; we’ve all been there. We can look at Lot’s decision and shudder, but who of us hasn’t been in an impossible moral quandary before? Still, Robinson makes clear that God is not condoning Lot’s choice in this story; after all, Scripture is a record of humanity—fallible, willful, and wrong as often as it is faithful, humble, and good.

I wonder if part of my discomfort in my younger years with the nuanced and gritty narratives of Scripture was the result of Christian nationalism whitewashing the origin stories of our country, leading to the belief that everything good must be completely good. Triumphalism and exceptionalism reigned in my conception of America, and thus, shouldn’t those hold true of God’s people, the Israelites?

But God is not a Christian nationalist (or any nationalist) kind of God. Rather than being interested in saving face, God allows Scripture to accurately portray the very mixed record of humanity, even the foibiles of the people God calls God’s own.

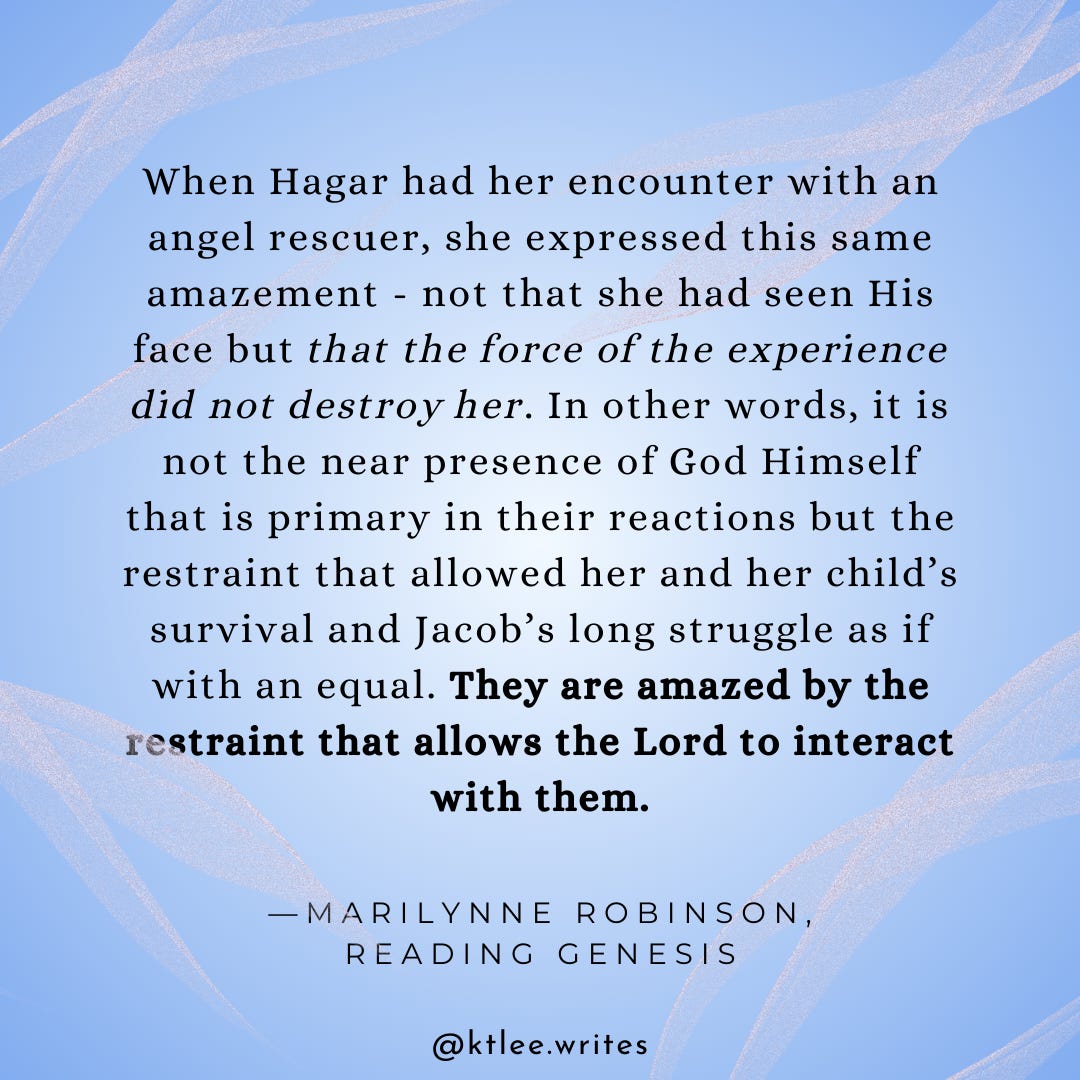

In fact, God’s responses to these human failures is what Robinson highlights most in Reading Genesis. It’s striking that God does not punish the wrongdoers of Scripture as they deserve, and this happens again and again throughout Genesis.

For those of us who can easily see grace in the story of Jesus but find it harder to unearth in the Old Testament, Robinson shows with example after example how God holds back in order to allow humanity to persist and to meet God.

Listening to Reading Genesis (I partly listened and partly read the physical book), I felt something within me revive, akin to how I felt when I first read Rachel Held Evans, but Robinson reached to the literary part of my soul. Robinson writes about Scripture with elegance and wisdom, her sentences complex and precise in a way that reminds me of Jonathan Tran’s, their intellects barely able to be contained in language.

It’s been 20 years since I first heard Scripture spoken of as literature. Whereas at the time, considering Scripture as literature almost broke my faith, ironically, now, reading the Bible as literature the way Robinson does helps me accept Genesis for what it is, not a series of prescriptive commands nor a record of heroic men, but the story of the faithful presence and the forebearance of a loving Creator who does not treat us as our misdeeds deserve. Over the years, my receptiveness to traditional Biblical commentary has diminished, turned off, I suppose, by too many contrived arguments or pat answers or tenuous connections, so I’m grateful that Robinson helps me approach the text with an open heart. I can trust her, it feels, because she’s not bending herself out of shape to prove a point.

Robinson writes, “I am as intent on magnifying the Lord as if I were a painter or composer, but my first obligation in commenting on the text is to be faithful to the text.”

This honesty—both regarding her intentions and her obligations—is compelling.

“No one wants to be found among the credulous,” Robinson writes, and I feel this in my bones. I am grateful for the disillusionment of my young adult days because the credulity of my youth was built on not asking tough questions, the kind of credulity that was fated to shatter. Yet here I am, found among the credulous once again, and I’m okay with it. It’s a credulousness borne of lonely wandering and throwing my tennis ball of a question at God again and again and again and having it bounce back and back and back and peering into canyons and crevasses and chasms and finally accepting that there is no certainty, there will always be mysteries, and that I have to make a choice.

Somewhere within me, I have hope that goodness will prevail. It’s the core message of Robinson’s Reading Genesis, which has renewed that hope in me. Even when it seems impossible, even when we can’t imagine how.

Someday.